What we requested from the parties

Based on the Law on Free Access to Information, we asked political parties in the Parliament for excerpts from all bank accounts of the head office, the Women’s Forum and municipal boards, as well as from the accounts for financing campaigns for parliamentary and local elections in 2019 and 2020. We also asked for all statements from foreign currency accounts and payment cards, as well as general ledgers of treasuries.

In all cases where the parties did not provide the requested information, we submitted complaints to the Agency for Personal Data Protection and Free Access to Information. In the case when the Agency did not make decisions within the legally prescribed deadlines, we filed lawsuits to the Administrative Court due to administrative silence, which took the position that political parties are reporting entities to the Law on Free Access to Information.

The parties further complicated the data analysis by first submitting partial data and then supplementing them. No party provided us with data in a machine-readable format and we manually transferred all the information obtained into electronic form so that we could analyze it. The balance on the account and the treasury, i.e. the number of statements from the bank account were used for verification, in order to ensure accurate data entry.

What we gathered from other sources

Audit reports of political parties compiled by the State Audit Institution (SAI) provided us with information on:

– bank account numbers of political parties;

– total revenues and expenses of political parties;

– the work of the treasury and the operation of municipal party boards.

Collecting of these data revealed that the detail of SAI audits is not uniform. In cases where audit reports were not available or sufficiently detailed, we took data from financial statements of the parties published by the Agency for Prevention of Corruption (APC).

From the APC’s website, we downloaded the official reports on the financing of election campaigns and bank account numbers of the parties that managed the finances and the special bank account. From that source and from the website of the State Election Commission, we determined which party participated in which elections and in which coalition.

What information we already had

We have previously collected data from the parties on the financing of the campaign for 2020 parliamentary elections, which include contracts with suppliers and invoices.

In what way we assessed the transparency of the parties’ financial operations

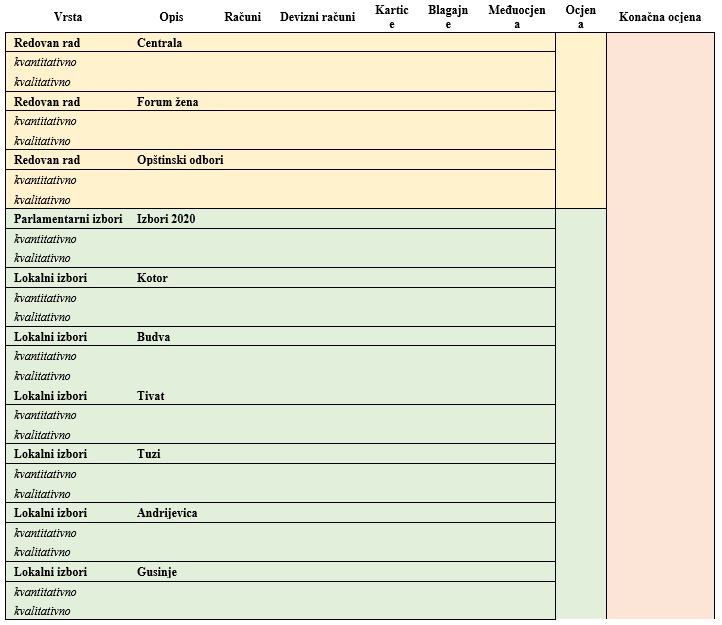

For each party, we created a separate table in which we assessed the transparency of financial operations, in relation to the individual types of data we received. Thus, the transparency of bank accounts, foreign currency accounts, payment cards and the general ledger were assessed separately. Each of these data was assessed separately, for the party head office, the Women’s Forum, municipal boards, but also in relation to individual election processes – parliamentary and local elections held in 2019 and 2020. Scores ranged from 0 to 5, where 0 means that the data were not submitted, and scores 1 to 5 assessed the scope and quality of the data obtained. The final score on the transparency of individual parties was obtained through the processing of scores in the transparency table.

What we requested from the parties

Based on the Law on Free Access to Information, we asked political parties in the Parliament for excerpts from all bank accounts of the head office, the Women’s Forum and municipal boards, as well as from the accounts for financing campaigns for parliamentary and local elections in 2019 and 2020. We also asked for all statements from foreign currency accounts and payment cards, as well as general ledgers of treasuries.

In all cases where the parties did not provide the requested information, we submitted complaints to the Agency for Personal Data Protection and Free Access to Information. In the case when the Agency did not make decisions within the legally prescribed deadlines, we filed lawsuits to the Administrative Court due to administrative silence, which took the position that political parties are reporting entities to the Law on Free Access to Information.

The parties further complicated the data analysis by first submitting partial data and then supplementing them. No party provided us with data in a machine-readable format and we manually transferred all the information obtained into electronic form so that we could analyze it. The balance on the account and the treasury, i.e. the number of statements from the bank account were used for verification, in order to ensure accurate data entry.

What we gathered from other sources

Audit reports of political parties compiled by the State Audit Institution (SAI) provided us with information on:

– bank account numbers of political parties;

– total revenues and expenses of political parties;

–the work of the treasury and the operation of municipal party boards.

Collecting of these data revealed that the detail of SAI audits is not uniform. In cases where audit reports were not available or sufficiently detailed, we took data from financial statements of the parties published by the Agency for Prevention of Corruption (APC).

From the APC’s website, we downloaded the official reports on the financing of election campaigns and bank account numbers of the parties that managed the finances and the special bank account. From that source and from the website of the State Election Commission, we determined which party participated in which elections and in which coalition.

What information we already had

We have previously collected data from the parties on the financing of the campaign for 2020 parliamentary elections, which include contracts with suppliers and invoices.

In what way we assessed the transparency of the parties’ financial operations

For each party, we created a separate table in which we assessed the transparency of financial operations, in relation to the individual types of data we received. Thus, the transparency of bank accounts, foreign currency accounts, payment cards and the general ledger were assessed separately. Each of these data was assessed separately, for the party head office, the Women’s Forum, municipal boards, but also in relation to individual election processes – parliamentary and local elections held in 2019 and 2020. Scores ranged from 0 to 5, where 0 means that the data were not submitted, and scores 1 to 5 assessed the scope and quality of the data obtained. The final score on the transparency of individual parties was obtained through the processing of scores in the transparency table.

Score “0“.

As already mentioned, from audit reports or from the financial statements of individual parties, which were somewhat more detailed, we determined whether the parties had treasuries, bank accounts of municipal boards, foreign currency accounts and payment cards. If the parties did not submit this information, and it is stated that they existed, they received a score of 0. However, for parties that did not have audit reports in the last two years, or did not provide details about any of this information (usually foreign currency account), we would consider that the information did not exist if the parties informed us in writing in response to our requests. If the parties did not respond to this request and provided other information, the score was 0.

While there is a possibility that parties do not have a foreign currency account, payment cards or a treasury, or operate exclusively through the head office without the involvement of municipal boards, all parties are required to have an account of the head office and the Women’s Forum.

In every elections in which parties participate, they must have accounts for financing the election campaign, except when they are a part of the coalition. In that case, the parties agree on which of them will manage the finances, so the data on the financing of the elections are with the chosen party, while the other members of the coalition do not have that information. Therefore, these parties cannot get an assessment of the transparency of the financing of those elections.

Assessment criteria

Scores were given using two types of criteria by which we assessed the scope and quality of available data. In the first place, we compared the submitted inflow and outflow data with the information from the audit reports, if they were compiled and contained that information. We then determined whether all excerpts had been submitted on the basis of the ordinal number of the excerpt indicated.

After that, we assessed the quality of available data based on the information that was available on suppliers and creditors, i.e. cash transactions. Without data on who paid the funds to parties, we are not able to see the sources of their financing, and without data on expenses, we cannot determine whether the expenses of the election campaign were paid. We also assessed whether the so-called intra-party transactions, i.e. transfers of money from one account to another owned by the party, could be determined from the submitted data. This is especially important because the inclusion of these inflows, i.e. outflows in the calculation of expenses and revenues fictitiously increases their amount, since it is essentially a transfer of funds between the party’s accounts.

Scores

We marked each of these criteria with a score from 1 to 5, where their fulfillment with over 95% gave a score of 5, over 75% a score of 4, over 50% a score of 3, and for score of 2, it was necessary to meet at least 25% of the set criteria. In this way, we obtained both qualitative and quantitative scores of the same data, and the lower one was entered in the table of transparency assessments.

After that, we calculated the intermediate score of the transparency of data from the head office, the Women’s Forum, as well as municipal boards and election accounts, in such a way that the assessment of each form of spending was evaluated according to its share in total spending. For example, if the spending of the party’s treasury in relation to the total spending was 6%, then the share of its score in the total score of the head office was as much.

For example: the party head office spent 100,000 euros through the bank account, 50,000 through the treasury, 20,000 through the business card and 10,000 through the foreign currency account. The total costs of the party are 200,000 euros, 50% goes through the bank account, 25% through the treasury, 10% through the card and 5% through the foreign currency account. In that case, the formula for calculating the transparency assessment of the party head office is: 0.5 x bank account score + 0.25 x treasury score + 0.1 x card score + 0.05 x foreign currency account score.

The intermediate scores thus calculated were used to calculate the next-order scores. For example, the assessment of the bank account, the Women’s Forum, the foreign currency account and payment cards was used to obtain the intermediate scores of the head office, and thus the intermediate scores of the Women’s Forum and municipal boards. These intermediate scores are then used to calculate transparency assessments of the regular party funding. According to the same principle, the percentage share of these three parts in the total expenses of regular financing is determined, and it is applied to the intermediate score of each of these parts.

According to the same principle, the assessment of the transparency of election campaign financing is calculated, followed by the overall assessment of the transparency of party financing.